Waste Not, Want Not at Plasco

June 5, 2013

By Treena Hein

The story of Plasco Energy Group seems almost too good to be true.

The story of Plasco Energy Group seems almost too good to be true. The company had only eight employees when it first approached the City of Ottawa in 2005, claiming it had the technology “to take garbage right off the back of the truck, without pre-treatment or drying, and convert it into electricity,” wrote Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson in his blog in late 2011, “…with lower emissions to air, water and land than putting the same garbage in the landfill.”

|

|

| From background to foreground, the MSW reception and sorting centre, the gasification system, and the bank of GE Jenbacher gensets that turn the gas to electricity.

|

Ottawa was certainly interested, providing the technology actually worked at full-scale. Plasco set to work on proving just that. It attracted more than $300 million in investment capital from within Canada, the U.S. and several parts of Europe to develop its waste conversion technology and build a demo plant. In 2008, Ottawa agreed to provide municipal solid waste (MSW) for that plant, and Plasco agreed to provide it with preferential terms for being an early adopter. The company also proved to the Ontario Ministry of the Environment that its technology could achieve extremely low emission levels. Plasco has grown to 160 employees over the past few years, and has spent more than $150 million in Canada to get to this point.

In December 2012, Plasco announced that it will build a facility in Ottawa, on a site leased to it by the city for a nominal fee. The plant modules will be manufactured in Ontario, with site construction and assembly creating about 200 jobs. Once operational, the plant will offer 42 permanent positions. Construction is expected to begin during late 2013, with startup scheduled for early 2015.

And that is only the beginning. “We have been selected for plants in China with a development cost of more than $2 billion and we are in negotiation for plants in other countries with development cost of another $500 million,” says Plasco president and CEO Rod Bryden. “The demand for this product is very strong.”

Inside the technology

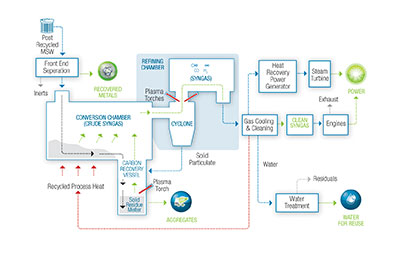

In short, rather than using plasma torches to burn garbage (what occurs in traditional incineration), the Plasco process gasifies waste and uses plasma heat only to refine the gases. This uses much less electricity.

In the first step of Plasco's patented ICARS system, MSW is converted into crude synthetic gas (syngas). This gas flows into a chamber where plasma torches are used to refine it, before it is cleaned to remove sulphur, acid gases and heavy metals. The clean syngas is used to power a series of GE Jenbacher generators, with net electricity sold to the grid. Continuous monitoring ensures there is sufficient syngas stability for the generators, regardless of the variations in the energy content of the waste.

There are no emissions to the atmosphere in the conversion process. Any unused syngas is sent to a flare. Exhaust from the engines and the flare have emission levels that the company states are “significantly below the most stringent standards in the world,” likening them to those “associated with ultra-low engine exhaust.” (Overall emissions data can be found on the Our Performance section of the company website, www.plascoenergygroup.com .)

In all, the process converts 95% of MSW to clean, valuable products. Moisture from the garbage is cleaned and made available for community reuse. Solid residue from the conversion chamber goes to a high-temperature vessel where plasma heat stabilizes it and converts any remaining volatile compounds and fixed carbon into crude syngas, which is fed back into the process. Any remaining solids are then melted into a liquid slag and cooled into non-toxic pellets that produce no leachate and meet requirements for a range of applications, including construction aggregates and abrasives.

Processing waste using Plasco’s system reduces greenhouse gas emissions in several ways. Sending garbage to Plasco eliminates the methane that would have been emitted through landfilling. Using the Plasco process also displaces the emissions that would have been created by power generation from sources such as coal or natural gas. Lastly, the company says the slag-pellet construction aggregate is in high demand and displaces the use of virgin aggregate, which requires the burning of fossil fuels for extraction.

Ottawa’s deal

Since the initial agreement in 2008, negotiations have continued between Plasco and the City of Ottawa to ensure that the facility will be built – and will operate – entirely at its own risk, notes George Young, Mayor Jim Watson’s senior communications advisor. “As a consequence, Plasco assumes all risk associated with fluctuating energy production and pricing, and the city will have no financial risk, contingent or otherwise,” he explains. “Overall, the City has taken a very conservative approach, negotiating a reduced size of plant and providing a buffer to maintain Trail Road Landfill economic operations.” Negotiations have also resulted in the creation of a dispute resolution process, and the selection of an alternative plant location with zoning already in place that’s compatible with the city’s Official Plan.

|

|

| From post-recycled MSW to electricity, the City of Ottawa hopes Plasco’s process will avoid the need for more landfill for decades.

|

Under a 20-year contract (with the option of four five-year extensions), Ottawa will annually supply 109,500 tonnes of MSW, with the right of first refusal to supply the balance of plant capacity (about 130,000 tonnes). The City will pay Plasco a tipping fee of $83.25 per tonne, escalating annually at the rate of increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This payment for taking feedstock – a major factor in Plasco’s business model – will provide the company with over $9 million per year.

By paying Plasco $9 million a year to convert its garbage, the City of Ottawa avoids having to create another landfill site, which would cost about $250 million. This balances out over almost 28 years. But Ottawa benefits not only by avoiding filling up its landfills and by cutting greenhouse gas emissions; it will share revenue with Plasco as well.

“The City will receive 25% of all revenues from any source after the company earns revenue which exceeds an agreed threshold,” states Bryden. Young says this bar for Plasco revenues in any one year is set at $34,100,000. “This figure is subject to adjustment post-commissioning to reflect the actual cost of construction of the facility, and annually to reflect CPI applied to operating costs included in the Revenue Baseline,” he notes. “In the event that annual revenue exceeds this adjusted Revenue Baseline, the city is to receive the first $822,500 above the baseline; Plasco would receive the next $2,467,500 and the two parties would share, on a city 25%/Plasco 75% basis, any annual revenues above $37,390,000.”

He adds that in recognition of the city’s commitment to Plasco and the development of this process, Plasco has offered the city a marketing fee to a total amount of $18 million, with an annual maximum of $3 million, to be paid based upon a $5 per tonne fee for all processing carried out in North America – excluding the first site constructed in California since this facility was confirmed prior to the agreement with the City of Ottawa.

Not that the process is without hurdles. In fact in late February 2013, Ottawa’s city council granted Plasco a five-month extension to complete financing and let out contracts on the plant, due to come on line in 2016. Still, council remains committed to the process.

“Plasco is the only technology operating today that can take mixed municipal solid waste as delivered from collection trucks and produce syngas to operate engines,” Young notes. “These engines are at least 30% more efficient than using steam to power turbines. While many technologies exist for clean biomass and wood, other technologies do not address adulterated biomass and the variety of materials found in waste.” He says the agreement with Plasco advances the city’s goals of maximizing waste diversion and reserving municipal landfill capacity for residential waste, should the technology prove successful. “It will also showcase Ottawa as a municipal leader in waste-to-energy tech,” Young points out. “This is not only an opportunity to showcase Plasco’s cutting-edge technology, but it also boosts Ottawa’s reputation as a place for innovation.”

“Furthermore,” Jim Watson noted in his blog in late 2011, “Plasco has created some of the most desirable kind of jobs for any city to attract – in engineering, process design, high-end fabrication…[It] has attracted the kind of jobs and innovation that have the potential to grow a new industry, to diversify our economy and potentially make a global impact.” At that point in time, Watson called Plasco “a potential world player, homegrown in Ottawa…poised to become very successful.”

With interest in the company burgeoning and contracts in China and California already secured, it seems his predictions are coming true.

Plasco plant Products

For every tonne of municipal solid waste (with an average calorific value of 14,200 megajoules per tonne) processed with the Plasco Conversion System, the following is produced:

- 1 kilowatt-hour of net electricity

- 300 litres of water for reuse

- 7 to 15 kilograms of metal (both ferrous and light metals like aluminum)

- 150 kilograms of slag (which can be used in place of quarried aggregates, such as sand to mix with portland cement to make concrete or as aggregate in asphalt)

Time to commission a Plasco facility (after all permits are obtained): 18 to 24 months

Generators: General Electric Jenbacher

Other equipment: Final decisions on suppliers have not been made.

Print this page