Remotely powerful: Nine rural communities’ experience with bioenergy – Part 4

August 18, 2020

By Sebnem Madrali and Jean Blair

A look at the communities’ training and capacity building

Blair Hogan educating visitors inside one of the energy centres in Teslin, YT. Photo courtesy Blair Hogan.

Blair Hogan educating visitors inside one of the energy centres in Teslin, YT. Photo courtesy Blair Hogan. [Editor’s note: this article is the last in a series of four. Find Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 online.]

The use of community-based biomass energy systems in rural and remote communities in Canada is relatively new, as indicated in the previous articles in this series, with most communities having only a few seasons of operational experience at most. This fourth and final installment in a series of articles focuses specifically on the nine communities’ needs and experiences related to the training of operators and capacity building.

The communities reported that training local operators and capacity building are critically important to the successful operation of community-based biomass energy systems. In most cases, local operators were involved with the installation process and learned about the technology as part of this process. Initial training on system operation was carried out by the system installer in all communities. Involving local operators in the installation and initial training was reported to be very effective in training the first round of operators.

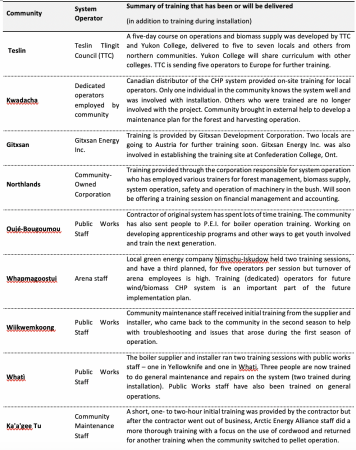

Follow-up and training new operators as the initial operators move on is more of a challenge, particularly in communities that do not have dedicated operators and high staff turnover. The communities have addressed this in different ways with varying degrees of success. Training efforts are summarized in the table below. In some cases, local operators have been sent to Europe to receive training directly from the technology provider or elsewhere in the country to train on boilers that were previously installed. The degree of initial and follow-up training and support from equipment providers and contractors are factors that should be considered when selecting suppliers and installers.

Details of system operators and training provided in the communities

Several communities have collaborated with, or are in the process of collaborating with, others in developing training materials. In the Northwest Territory, for example, where there are many biomass installations, the territorial government recently developed a biomass boiler training module aimed toward operators that is delivered through their School of Community Government. No other province or territory has developed any sort of training program and many respondents expressed the need for a more coordinated approach to training. Depending on the nature of the supply chain, training may also be needed for drivers, forest harvesters and log yard operators.

All nine interviewees agree on the importance of hands-on training and would like to see at least a portion of any training program be carried out in a community with an operational biomass system. In Northlands, Gitxsan, Whapmagoostui, Oujé-Bougoumou and Teslin, the interviewees themselves (all consultants) have been instrumental in establishing training programs for biomass system operators. In both Oujé-Bougoumou and Northlands, training includes not only technical aspects of biomass boiler operation but also soft skills such as financial management, human resource management and reporting.

In communities where the biomass systems are operated by community maintenance or public works staff, challenges related to high turnover of maintenance staff and ensuring a trained staff member is always available – especially during hunting season – were expressed by most communities.

For systems with a local feedstock supply system, where the log yard and chipper also need to be managed, having dedicated staff, ideally employed by a corporation established specifically to operate the system and act as a utility, was noted by all respondents as being crucial. This entity may be owned by the community but must be financially independent in order to have money available when needed. In some communities, this entity is also responsible for organizing and/or delivering training.

Responses from the nine interviews suggest that the ripple effects of biomass systems include the stimulation of interest of locals and opportunities for learning and capacity building that did not previously exist within the communities. Communities that harvest biomass locally have generated significant economic and employment opportunities for locals, many of whom were previously unemployed. Work in the bush can generate a source of income for dozens of people in the community, while operating the log yard, chipper and boiler has created four to six steady jobs in all communities that use locally-harvested wood chips. In general, the skills required to harvest and supply the wood fit well with skills that community members already possess but are not often paid to use.

Many respondents commented on how well mechanically-inclined local operators have been able to troubleshoot and overcome technical issues on their own. When pellets are used, fewer employment opportunities are created but maintenance staff do get to learn new skills and there are opportunities for jobs related to fuel logistics and delivery. In Wikwemikong and Gitxsan, a local biomass distribution system has been established to provide local bulk delivery. This generates notable economic opportunity and can lead to the development of more biomass projects due the availability of bulk fuel for smaller scale projects.

Concluding remarks

Biomass systems provide remote communities with new opportunities for employment and education that could have a very positive impact over the long term but training, staffing and scheduling is a challenge and requires working with local values and traditions. The skills required along the biomass supply chain are a good fit with the local skill base. Ongoing training of operators is essential, particularly if there is no dedicated operator and staff turnover is high. However, each community had to figure out how to deal with the initial and ongoing training on their own or with the help of the boiler installer/supplier on one-on-one basis. There is a collective hope that, in the future, a more standardized and co-ordinated regional approach to training will be established. For this to happen, support from higher levels of government and educational institutions will likely be required.

Looking ahead

Almost all of the 250 or so remote and rural communities in Canada can benefit from bioenergy to meet their heat and power demands. The number of bioenergy systems in remote and rural regions are currently small but indications suggest significant growth. An ongoing project led by CanmetENERGY aims to increase the acceptance and implementation of heat and combined heat and power (CHP) systems using biomass fuels in rural and remote regions of Canada. Long-term, reliable, and safe implementation of bioenergy technologies requires long-term vision and plan for the development of local, trained capacity in partnership with local colleges, communities, equipment suppliers and governments. To that end, CanmetENERGY plans to build on the recently completed interviews and expand it to include operators, other communities, equipment suppliers, biomass fuel suppliers and local colleges and government agencies. If interested, please contact Sebnem Madrali at CanmetENERGY via sebnem.madrali@canada.ca.

The authors wish to thank all nine participants for providing details about their projects and agreeing on sharing publicly. We also acknowledge the funding support received from NRCan’s PERD program.

This article is part of the Bioheat Week 2023. Read more articles about bioheat in Canada.

Print this page