Season of tragedy – the grain elevator explosions of 1919

June 24, 2021

By Rose Keefe

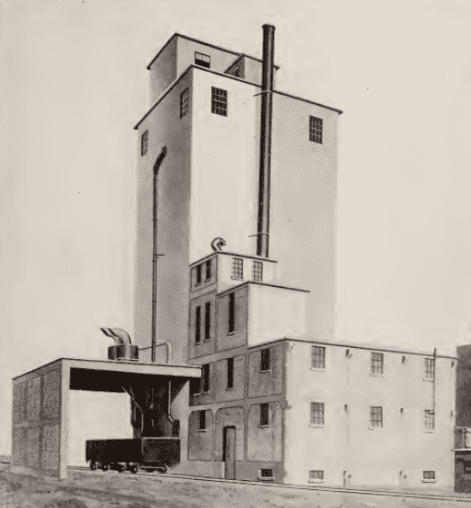

The Smith-Parry Grain Elevator in Milwaukee, Wis. Photo courtesy The American Elevator and Grain Trade.

The Smith-Parry Grain Elevator in Milwaukee, Wis. Photo courtesy The American Elevator and Grain Trade. If an incident happens twice, it could be a coincidence. If the same sort of incident happens four times over a five-month period, there is something wrong.

Between May and September 1919, four grain elevators in four different North American cities exploded in similar incidents, killing 70 people and injuring 60 more. This doesn’t look like a coincidence.

The fact that four similar dust explosions occurred over a matter of months raises two critical questions: Why so many? And why did they all happen so close together?

Although these incidents occurred over 100 years ago, the answers are still relevant today. For example, if World War I and the Spanish Flu impacted grain handling practices, those issues may arise again during COVID-19, when social distancing requirements may be reducing the number of workers on site or returning to site and, by extension, attention to safety.

This study examines the factors that may have contributed to these 1919 grain elevator explosions. Identifying commonalities could prevent similar tragedies from happening in the future.

Combustible dust incident #1: the Milwaukee Works explosion

On May 20, 1919, at 11:15 a.m., a dust explosion at the Smith-Parry Grain Elevator in Milwaukee, Wis., killed three men and seriously injured four others.

It was a newer structure, having been built in 1917 to produce animal feed, and included a 100’ by 20’ crib for handling popcorn. Both the mill and warehouse were concrete and considered state-of-the-art for the time.

A 15-year-old boy recalled that he had been moving bags of grain when the explosion shook the elevator building and ignited flames everywhere around him. He escaped by jumping through a grain chute, but seven of his fellow workers weren’t so lucky.

Investigators concluded that the explosion occurred when sparks from machinery friction ignited grain dust.

Once their findings were published, the press quickly moved on to other, more sensational, stories. The incident did not get a lot of attention outside the local press due to the comparatively low death count. During the early 1900’s, injury and death were accepted as occupational hazards in industries like coal mining and grain handling, and unless a lot of casualties resulted, dust explosions did not attract a lot of attention.

Unfortunately, things were about to get worse.

Combustible dust incident #2: the Douglas Starch Works plant explosion

On May 22, 1919, at 6:30 p.m., a small fire ignited cornstarch inside the Douglas Starch Works plant in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The resulting explosion killed 44 people, injured 30 more, and leveled the entire facility. Over 200 homes in the vicinity were damaged and some debris landed two miles from the site.

The economic loss was equally huge. Founded in 1903, Douglas Starch Works was the largest starch works company in the world by 1914. The plant and its elevator employed 650 to 700 people in 1919, making it a major employer for the city.

At the time, there was very little regulation for factories that handled or produced combustible dust.

The losses from this incident were so high that Iowa citizens demanded more government attention to fire and workplace safety laws. Their concerns were inspired by comments about questionable safety practices at Douglas Starch Works. One day shift worker had told reporters that men in the plant persisted in smoking around the buildings despite supervisor warnings.

Commenting on the explosion in an issue of the National Underwriter, Joseph Hubbell, manager of the National Inspection Company of Chicago, opined that it occurred in the plant’s wet process buildings, where some dry starch may have built up.

“It is now ascertained that projecting air blasts through the doors and conveyors connecting these sections filled them with a starch dust cloud, caused by smashing and upsetting of conveyors, packages, bins, and the like, and went to the end with increasing speed and compression until the building structure gave way.”

On May 27, the coroner’s inquest jury found that the victims had been killed by a “fire of unknown origin followed by an explosion.” No one was ever held criminally responsible for the disaster.

June and July passed without any incidents. Then, on a warm August day in Port Colborne, Ont., a third explosion took place.

Combustible dust incident #3: the Port Colborne Grain Elevator explosion

The Aug. 9, 1919, explosion at the Dominion Grain Elevator in Port Colborne killed 10 workers and left 16 others with serious injuries. Total damage was estimated at $1.5 million Canadian dollars.

Opened in 1908, the elevator played a central role in grain movement throughout the Great Lakes. It was made from reinforced concrete and had a capacity of over two million bushels after more storage bins were installed in 1913.

On the day of the explosion, a fire occurred in one of the lofters used to transfer grain from the lower to the upper system of the elevator’s horizontal conveyors.

Workers put it out, but smelled burning rubber when they returned from lunch. Assuming that a belt in the basement had overheated, they did not investigate.

At around 1:00 p.m., two men saw smoke issuing from the motor of the conveyor in the lofter head area. Fifteen minutes later, a man working on the top floor saw smoke and fire on one of the belts and made it down to the first floor just before an explosion erupted.

The explosion blew apart the top three floors, lifted the concrete roof, and hurled wreckage over a mile away.

Investigators believed that heat from the motor of the jammed conveyor had ignited airborne dust, causing it to explode. However, the law may have also played a role in the Port Colborne explosion.

Canadian regulations prohibited the removal of dry dust from processed grain – if an elevator received 500 tons of grain, the same amount had to be shipped out, even if much of it was grain dust. When the dust leads for the bins in the Dominion Grain Elevator were closed to reduce any product loss, the fans could not clear away airborne particles, creating prime conditions for a dust explosion to occur.

Industry leaders in Ontario were still debating this conundrum when the fourth and final explosion took place.

Combustible dust incident #4: the Murray Grain Elevator explosion

At 2:10 p.m. on Sept. 13, 1919, the Murray Grain Elevator in Kansas City, Missouri was destroyed by a dust explosion that killed 14 men, injured 10 others, and caused $650,000 worth of property damage.

On Sept. 5, 1919, an inspector for the U.S. Grain Corporation found dust accumulated everywhere, along with ignition sources like worn extension cords, carbon filament lighting, and lack of protection on electric light bulbs. There was only one partially filled fire extinguisher on the top floor.

When questioned, the superintendent tried to explain away the dust piles by saying that the dust collector’s fan had recently broken down, but the inspector had personally seen it working. In his report, he wrote, “This plant is dangerous and even though fireproof, will explode if its present condition is permitted to exist.”

On Sept. 12, another inspection took place, but conditions had not improved. Now worried about the possibility of sanctions, elevator management ordered a clean-up the next day, but it was too late.

At around 2:10 p.m., a maintenance man saw blue flames shooting out of electric light wires seconds before an explosion tore the building apart. The force was so tremendous that the entire working shed was blown away and pieces of the 16-inch concrete wall were later found several feet away from the elevator grounds.

Firefighting efforts were delayed because the nearest hydrant was 8,000 feet away. It took over an hour for the fire department to create a long enough hose connection. During that time, the flames had spread from the elevator itself to 30 grain-filled boxcars at the south end of the property.

After inspecting the damage and interviewing witnesses, investigators concluded that the explosion originated in the basement and propagated up through the manlift tower. On Sept. 19, the coroner’s jury ruled that the cause of the explosion was unknown, although the maintenance man repeated his story of seeing blue flames coming out of electric light wires. There were also allegations that someone had lit a cigarette in an area not designated for smoking.

The Murray Grain Elevator explosion appeared to have drawn attention to substandard safety practices in North American grain elevators, because fire underwriters and insurers who had considered fireproofing to be sufficient protection were now re-inspecting facilities for dust explosion hazards. Managers who formerly resented and resisted these intrusions now welcomed them.

What caused these dust explosions in grain elevators?

Although dust explosions in grain handling facilities weren’t rare in 1919, four devastating events over a period of five months is abnormal and raises the question: what caused them?

In this section, we review factors, a few of which are relevant even today, that may have contributed to this string of tragedies or made them worse. They are:

- Grain elevator construction

- Unsafe work practices

- Current events (in this case, the Spanish flu and conclusion of World War I)

Grain elevator construction

Before 1905, grain elevators were made from cribbed timer or sheet iron on a frame. These structures vented explosions more easily, so they suffered more from fire damage. Believing that the solution was a ‘fireproof’ structure, designers and builders shifted from wood to concrete.

The problem was that an all-concrete grain elevator was a bigger explosion risk than its wooden predecessors. In addition to the three elements of the fire triangle (heat, fuel, and an oxidizing agent), dust explosions require confined space. Although the industry believed that a heavy concrete elevator could safely contain an internal explosion, it was quickly proven wrong.

With the explosions at Douglas Starch Works, Dominion Grain Elevator in Port Colborne, and the Murray Grain Elevator, the elevators not only blew apart, but pieces of the concrete structure were found miles from the site. Without proper venting, the force of each explosion caused irreparable damage.

Despite these tragedies, faith in the invincibility of concrete elevators continued for years.

The Armour Grain Elevator in Chicago, touted as the ‘world’s biggest elevator,’ was considered so safe that its owners deemed insurance unnecessary. Their confidence was misplaced: in 1921 the elevator experienced a grain dust explosion so intense that 40 of its loaded concrete silos shifted six inches on their foundations. Six people died and losses were estimated at $3 million.

Investigations into the root causes of these explosions gradually led to improvements in elevator design, such as venting and isolation of more hazardous equipment. Unfortunately, these safety measures came too late for the victims of the 1919 explosions.

Unsafe work practices

During the early 20th century, only a small number of workers (many of them part-time or seasonal) were needed to operate a large grain elevator. Quick processing of high volumes of grain was essential to realize a return on investment. Consequently, cleaning and maintenance went by the wayside because it siphoned away necessary labour without boosting profits.

Other problems that contributed to grain dust fires and explosions then and now include:

- Welding or cutting operations in poorly-ventilated areas

- Open flames, including matches used to light cigarettes

- Improper attention to slipping elevator belts

- Dust coming into contact with hot surfaces like bearings

- Friction sparks from machinery or tramp iron (which caused the Milwaukee Works explosion)

- Electric arcs from static, surges, cable damage, or improperly applied electrical equipment (which is believed to have caused the Murray Grain Elevator explosion)

In 1919, National Fire Protection Association (AFPA) guidelines were treated as optional and likely to be ignored if implementation was expensive.

This tunnel vision continues to be a problem today. Cost often takes priority over safety when implementing fire and explosion safety measures, and until this practice stops, the danger will never be overcome.

Current events

World War I

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, over 4.7 million men and women served in the regular U.S. forces, National Guard units, and draft units, with around 2.8 million serving overseas. By the time peace was declared, 115,600 had been killed and 200,000 wounded.

In Canada, more than 650,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders served: out of this number, more than 66,000 died and more than 172,000 were wounded.

These soldiers surely included skilled agricultural workers who understood the fire and dust explosion risks in grain handling facilities. Whoever replaced them may not have had the same level of knowledge and experience.

At the same time, demand for wheat increased. Farmers were encouraged by the government to ‘Win the War with Wheat.’ The crops were not just for Americans – a lot of them went to Europe, where the war had drastically impacted wheat production. Demand for output, combined with a workforce impacted by the war and Spanish flu (see below) conceivably resulted in safety missteps that proved fatal.

The Spanish Flu

Several comparisons have been made between the COVID-19 and Spanish Flu pandemics. Both are respiratory illnesses caused by a virus, transmitted through close contact, and spread across the world within months, killing millions.

Pandemics of this magnitude affect workforces everywhere. Illness-related deaths and absences, combined with social distancing, can result in a workplace with fewer skilled workers who understand the dangers of their specific industry.

With the Douglas Starch Works and Murray Grain Elevator explosions, there were allegations of smoking in high-risk areas, something that experienced and aware workers probably wouldn’t have done. Minutes before the Dominion Grain Elevator exploded, men returning from lunch smelled something burning but failed to investigate.

Lessons learned

Jess McCluer, vice-president, safety and regulatory affairs at the National Grain and Feed Association (NGFA), observed one important commonality between all four incidents.

“There wasn’t any type of program in place to mitigate ignition sources, i.e. smoking, sparks or explosion hazards [such as] dust accumulation,” he says. “Further, there wasn’t any type of plan to address the heated bearings in many of the conveyors i.e. preventative maintenance.”

These mistakes shouldn’t be blamed on the workers. Then, as now, they carried out their duties under the direction of elevator management. With demand for wheat being high despite personnel shortages due to the war and the pandemic, safety may have taken a back seat to production and profit.

Conclusion

Regulations and safe work practices are necessary to encourage conformance to appropriate standards in grain elevator design and construction. Industries and countries without appropriate and enforced regulations may continue to see combustible dust incidents.

Although design changes and advanced protection systems now mitigate losses in grain elevators in North America, COVID-19 has affected the industry globally, much like World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic did. Due to social distancing, many locations have fewer workers on site and, as we return to work, see an increase in new personnel to replace those who have died of COVID. The changes in routine and inexperienced new hires may contribute to a lack of focus on fire and explosion dangers.

Although we can’t totally escape conflict and disease, we can prevent them from affecting safety in industries handling combustible dust. We can also work together on an international basis to encourage appropriate standards and safe work practices around the world. Ensuring that safety remains a priority at all times can lessen the human cost of these tragic events.

Sources

Periodicals

- Wausau Daily Herald (Wisconsin)

- Decatur Herald (Wisconsin)

- Portage Register-Democrat (Wisconsin)

- The Cedar Rapids Gazette (Iowa)

- Ottawa Journal (Ontario)

- Kansas City Star (Missouri)

- Kansas City Times (Missouri)

Publications

- The American elevator and grain trade. (1917). Chicago: Mitchell Bros. & Co

- Proceedings of conference of men engaged in grain dust explosion and fire prevention campaign, conducted by United States Grain Corporation in cooperation with the Bureau of Chemistry, United States Department of Agriculture. (1920). New York: U.S. Grain Corporation.

Rose Keefe is a technical writer for the DustEx Research family of services including DustSafetyScience.com.

Print this page