Waste not, want not

February 12, 2014

By

Amie Silverwood

As the largest urban centre between Winnipeg and Sudbury, Thunder Bay has two post-secondary institutions that are deeply invested in developing the region’s potential for making heat from wood.

As the largest urban centre between Winnipeg and Sudbury, Thunder Bay has two post-secondary institutions that are deeply invested in developing the region’s potential for making heat from wood. The region’s geography, climate and economy feed the faculties’ obsession with the forest’s bounty. The problems they’re working to solve could strengthen local economies, provide heat and electricity to northern communities, and bring jobs and training to those in remote communities. However, their work is butting up against regional politics, risk-weary industries and a public that doesn’t understand the potential in the piles of wasted wood on the roadsides.

|

|

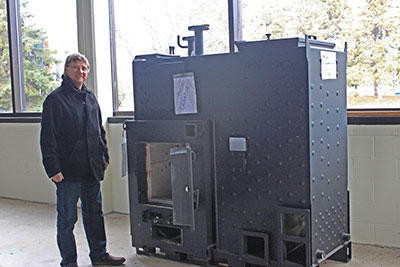

| Brian Kurikka stands beside the BioEnergy Learning and Research Centre. It will be used by students, faculty, researchers and anyone interested in biomass heating as a demonstration and training facility. Froling and Evergreen bioheat (Froling’s Canadian Distributor) can train in Thunder Bay rather than sending its people to Austria.

|

On the northern shores of Lake Superior, Thunder Bay is a regional centre that serves as a hub to very remote communities scattered throughout Northwestern Ontario. Many of these communities are completely isolated and can only be reached by air or via ice roads in winter. Crippled by unemployment and highly dependent on trucks to bring in heating oil or propane for electricity generation, these villages sit within a vast, rich forest that could provide heat, electricity, jobs and more if they’re able to tap into the opportunity.

Canadian Biomass sat down with a group of researchers from Confederation College and Lakehead University in Thunder Bay to discuss the headway being made in the region and how their research can relieve pressures on remote communities. We also had the opportunity to tag along with Resolute Forest Products to see how researchers have collaborated with local industry to make a more resilient bioeconomy.

Finding a use for waste wood

Anyone who works in forestry in the region knows about the piles of debris made up of tree tops, small branches and other material that is unwanted at the sawmill or pulp and paper mills. But knowing exactly how much material there is, the best use for it and what kind of environmental impact would result from its removal is important for companies like Resolute.

Resolute has recently converted a boiler at its pulp and paper mill to this waste material to generate electricity: powering the plant and selling it back onto the local power grid. It has also reached an agreement with Atikokan Power Generation to supply 45,000 tonnes of pellets annually. But before a company like Resolute can make the capital investments required to diversify its operations in this manner, it must be confident that it has access to enough material to feed the investment.

“To have Lakehead University and Confederation College here for us is a huge benefit,” explains Martin Kaiser of Resolute Forest Products. “They helped us particularly in the early stages when we were doing things like trying to prove how much biomass was out there. They did a lot of work that was really valuable on the fuel qualities, characteristics of bark, the different components of tree species and different species for burning.”

Biomass to burn

When a logging contractor harvests a stand of trees, he or she cannot pick and choose only the most valuable sawlogs; the forest must be managed according to regulations designed to help it regenerate without altering the mix of tree species therein.

|

|

| Brian Kurikka displays the new 150-kilowatt research boiler that will be housed in the BioEnergy Learning and Research Centre at Confederation College.

|

“The boreal forest regenerates by disturbance,” says Brian Kurikka of Confederation College. “Naturally that was fire. If you’re going to suppress fires, you’ve got to harvest it. If you leave the birch standing, they’ll die in an exposed cutover. And then it doesn’t regenerate very well. If you harvest it, new growth starts.”

Birch trees currently don’t have a lot of value in Northwestern Ontario due to their size and quality. Generally they are chipped and used for biomass but many stands of trees wouldn’t be cut at all because of the species mixture and distance from the pulp mill – there wouldn’t be enough merchantable wood to make the harvesting of it profitable. Finding a value in the unwanted wood makes for a healthier industry all around.

Colin Kelly, Director of Applied Research at Confederation College, is looking at the value chain of the forest. “There’s as much biomass out there that was never harvested or left at the roadside or in the bush as the province harvests for commercial purposes. So a lot of people define that as the opportunity: there’s millions of cubic metres of fibre that could be used for something but isn’t.”

Instead of burning the slash piles at the roadside (an unpopular management system) or returning it to the bush (a labour-intensive job), Kelly suggests taking the biomass from the leftover tree trunks and large branches and leaving only the small branches and leaves that contain 90 per cent of the tree’s nutrients. With the small branches and leaves left to replenish the soil, the forest has everything it needs to regenerate while the biomass can be used to heat homes or generate electricity.

Because of the region’s long heating season, the potential for district heating is huge. The college serves a lot of remote communities that rely on heating oil or propane to be trucked in with the profits going to the large petroleum multinationals. Converting to district heat would keep the money in the community, develop transferable skills among the unemployed and have the environmental benefits of dramatically reduced emissions.

“What’s been holding it back, from our perspective, is regulatory environment,” says Kelly. “Access to Crown land, access to fibre, building and industrial codes, air emissions – there’s just a whole slew of anti-wood regulations out there because the regulations were designed in Southern Ontario with no idea what the impacts would be in Northern Ontario.”

When the college decided to install biomass-fuelled heating units, the approval process was arduous – it would have been much easier to install diesel generators since all diesel generators on the market have been preapproved. “We want to get the biomass industry to that point. If you go buy a commercially prepared biomass heating unit, you don’t have to worry about an air emissions permit, why would you? It’s cleaner than a diesel unit!”

In remote regions, complex systems don’t work because they’d require access to an engineer for maintenance. Any system adopted in a northern community should not require special training to run and maintain. These simple heating systems exist and can take up to 30 per cent of the load off the electrical systems that are currently at their limits during the peak season – winter.

Kurikka recommends woodchip-fired district heating in forest-based communities – a system that can be more economical than pellets though not as efficient because chips have a higher moisture content than pellets. But chippers are common, easier to operate and don’t require a large capital investment, unlike pelletizers, and the fuel supply opportunity remains in the community.

The resources are plenty, research has been done to support the sustainability of producing heat and electricity from waste wood and the economic case is clear. The hurdles that remain are primarily based on public perception but with Ontario Power Generation, Resolute Forest Products and Confederation College moving forward with biomass projects, the tide is turning.

Confederation College builds a bioenergy centre

Confederation College is in the process of building a learning and research centre that will be able to test different wood fuels, boilers and emissions, and act as a training facility. It includes a solar wall that will preheat the intake air for the boilers to further enhance efficiency. Two 500-kilowatt Froling boilers will be heating the 400,000-square-foot main building on campus while also providing information for researchers interested in biomass heat for an institutional application, a small community or a large warehouse.

A smaller 150-kilowatt unit will be dedicated for teaching, demonstration and research. It will have a stand-alone fuel system designed for hopper containers that can be sent to fetch various test fuels. The stand will be placed on load cells that can monitor how much fuel is used in real time.

The building is large and roomy to accommodate students and faculty and will be used to demonstrate and train on biomass heating equipment ranging from 500-kilowatt institutional sized units to small residential housing units.

The storage room will include a walking floor that will move the material up to fall into the trench where it will be fed into the boilers. At peak load, the storage room will include a three day’s supply of wood chips with a moisture content in the 35 per cent range. The chips will be supplied by an urban forestry company that chips wood from Thunder Bay trees at a local wood diversion yard.

The student lab will include primary equipment to check biomass moisture content and sizing for basic tests and advanced boiler and emissions monitoring equipment.

Print this page