Residual effect – Boisaco optimizes mill byproducts

July 28, 2016

By Guillaume Roy

Aug. 10, 2016 - In the 1970s, building a sawmill in Sacré-Cœur, Que. – a village of 2,000 residents in the Cote-Nord region – seemed like a good idea to create jobs and develop the local economy. But it took three bankruptcies before a group of visionaries made it work.

Boisaco would like to transform 100 per cent of the logs that come to the site into an end product. In the 1970s

Boisaco would like to transform 100 per cent of the logs that come to the site into an end product. In the 1970s

In 1985, two worker cooperatives, Unisaco and Cofor, united their efforts to fund Boisaco, a softwood sawmill. A local investment fund of 421 shareholders, Investra, also joined the venture. From the beginning, the sawmill made good money, but the leaders were not satisfied.

“We wanted new ways to create more wealth in the community,” says Guy Deschènes, one of Boisaco’s founders and the former CEO.

To create that wealth, the company decided to look at ways to diversify the use of its byproducts, such as wood chips, sawdust and shavings.

Marc Gilbert, Boisaco’s general manager from 1985 to 1998 and from 2008 to 2012, says that the sawmill was often far away from its buyers, which made it difficult to sell the mill’s residual products. So instead of continuing to look for ways to sell some of its residuals, the company decided to produce new products.

In 1999, Boisaco launched a new door panel mill, Sacopan. Two years later, they made a partnership with the American giant Masonite, to help enter new markets. This allowed the sawmill to use 35 per cent of its wood chips on its industrial site. But it wasn’t enough. In 2002, they created Ripco, a joint-venture between Boisaco and Royal Wood Shavings, a company that specializes in animal products distribution.

“Royal Wood Shavings takes care of marketing and distribution and we take care of operations,” explains André Gilbert, Boisaco’s general manager. “We could have bought the operations but we prefer to have a strategic partner. We are stronger together.”

Building partnerships is how Boisaco developed all of its sister companies.

To make high-quality horse bedding, wood shavings are blown from the planer to the packing area via an aerial system.

The company has one market for its big shavings, another for its medium-sized shavings and the dust goes to the small animal market (the dust sifted out because some horses are allergic to wood dust). This byproduct venture generates more than 800,000 40-pound bags of horse bedding annually, and has created jobs for 15 people.

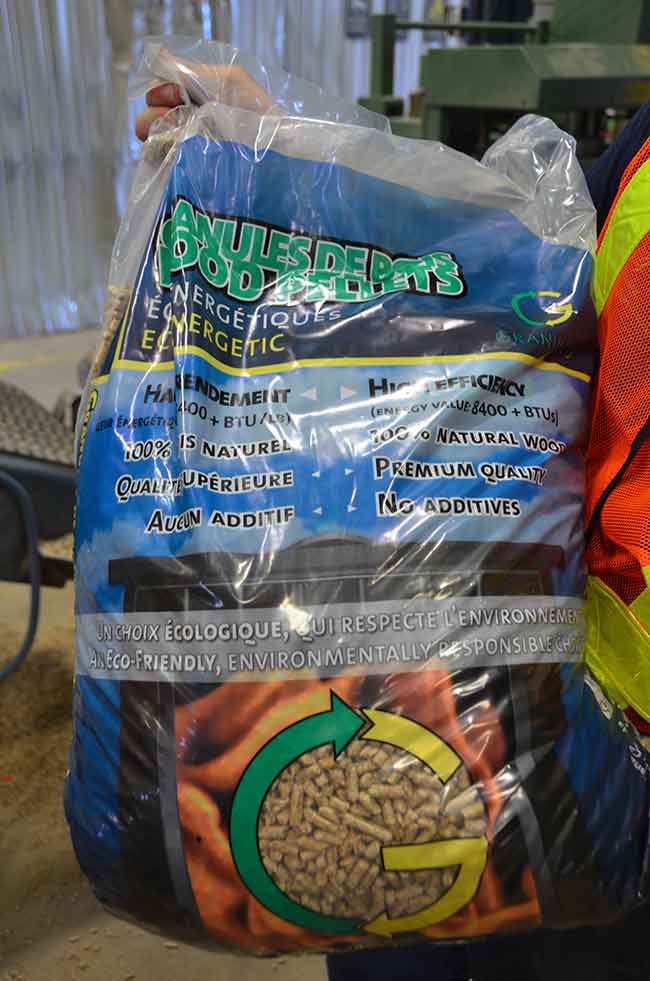

With an annual production of 550,000 m3, Boisaco still had some byproducts left. So to use 100 per cent of the sawdust and shavings, they made a plan to build a wood pellet plant. Even when the markets deteriorated during the financial crisis in 2008, Boisaco decided to go ahead and create Granulco in 2009 – a wood pellet company built on Boisaco’s sawmill site.

To make this new business flourish, Granulco entered into a joint venture with Essipit, a nearby Innu First Nation, and la Société de développement économique de Sacré-Coeur.

Last year, Granulco made 1.25 million 40-pound bags and some bulk sales to reach a 25,000-ton production, still short of the facility’s 35,000-ton capacity.

“We don’t produce enough sawdust to use Granulco’s equipment at 100 per cent,” says Éric Gravel, Boisaco’s quality and production superintendent.

To fill the gap, they started using poplar sawdust produced by Bersaco – another sister company 28 kilometres away – but they stopped using it after customers complained about the smell generated by the use of poplar.

To ensure the samwill’s byproducts are sent to the best application, the mill installed a 8’ x 4’ Forano chip screen that separates the different chip sizes.

The small chips go to the company’s Sacopan door panel company, while the large chips are sold to pulp-making businesses, and the sawdust goes to Granulco or Ripco.

“Everybody wins, because pulp and paper mills prefer big saw chips,” Gravel says.

Before entering the pellet mill, the sawdust goes through a biomass dryer, using up to 15 per cent of the resource. Burning the poplar sawdust helped for a time, but carrying the material did not make economic sense, long-term.

After being dried, the dust is sent to its Pioneer pellet mill, cooled and finally bagged. With increasing popularity of residential biomass heating systems in Québec, Granulco sells nearly almost all of its production in advance.

“Our biggest client, Rona, would like to buy our entire production, but we prefer to have many clients – it would be too dangerous to rely on only one,” says Eddy Gauthier, Granulco’s general manager, who supervises a group of 15 employees.

Location, location, location…

For Granulco, being on the same site as the sawmill makes the transportation costs go down to nearly zero. But it’s not the only advantage.

“All together, we qualify as a big enterprise and we have access to the industrial price – Tariff L – with Hydro-Québec. This nearly cuts our utility bill in half,” Gilbert explains.

All the mills also share professional services, specialized equipment and storage areas.

“A small business like Granulco could not hire full-time mechanics, but we can share the cost of those professionals,” Gravel explains.

The sawmill also produces all the wood pallets and other components needed by its industrial partners. All these extra products create more jobs and additional wealth for the community. Since different shareholders own the companies on the industrial site, all the products are sold at market price.

“The wood products market is always going up and down. Other sectors, like door panels and pellets, now make Boisaco a more stable and more profitable business,” Gilbert says.

This model now stands out. While some forest communities are struggling, Sacré-Coeur is in better shape than ever and is willing to keep building its future with timber. The different companies on the industrial site now employ over 550 people, the equivalent of more than 25 per cent of the entire Sacré-Cœur population. The tax income from the site also accounts for 30 per cent of the town’s $3-million municipal budget.

Projects ahead

Boisaco currently uses 70 per cent of the 60,000 tons of bark produced on the site to heat the mills on site and dry the different products, but they want to create extra value with the remaining 30 per cent (and the bark built up over time). So they have begun another project with another partner, a 9-MW cogeneration mill with Hydromega, an independent renewable resource energy producer. The project is planned for 2019.

Even with all those businesses, Boisaco will still be left with 65 per cent of its woodchips being sold outside the industrial site, primarily to pulp and paper companies like Resolute Forest Products. Going forward, the company would like to continue building new products with its remaining residuals. It is currently reviewing emerging technologies for developing a bioenergy or green chemistry project. Ideally, Boisaco would like to transform 100 per cent of the logs that come to the site into an end product, and if the mill continues to find homes for its residuals that dream may one day be realized.

Print this page