Remotely powerful: Nine rural communities’ experience with bioenergy – Part 1

July 28, 2020

By Sebnem Madrali and Jean Blair

Wood chip processing facility in Teslin Tlingit First Nation. Photo courtesy Blair Hogan.

Wood chip processing facility in Teslin Tlingit First Nation. Photo courtesy Blair Hogan. [Editor’s note: this article is the first in a series of four. Find Part 2 here.]

Nearly three quarters of Canada’s 250 or so remote communities currently rely on diesel generators to produce their electricity, prompting efforts from government, NGOs and communities to displace diesel by integrating renewable energy technologies. Although important, these integrated generation systems only address a small portion of communities’ energy needs, as a large portion of energy demand is attributed to space heating and domestic hot water requirements. Generally, these heating loads are met by oil, diesel or propane-fuelled (and, in some cases, electric) furnaces.

Modern biomass heating systems – in individual buildings or connected to a district energy system – are one of the few clean and renewable options for displacing fossil fuels used to meet heating demand in remote northern communities. Several diesel-dependent communities in Canada’s north have recently adopted biomass heating or combined heat and power (CHP) technologies. This number is expected to grow in the near future.

As the application of bioenergy in remote communities grows, it is important to gain a better understanding of what has or has not worked in terms of fuel supply, technologies and system design. This will help guide future research and development efforts, and streamline the development of biomass heating and CHP in other communities.

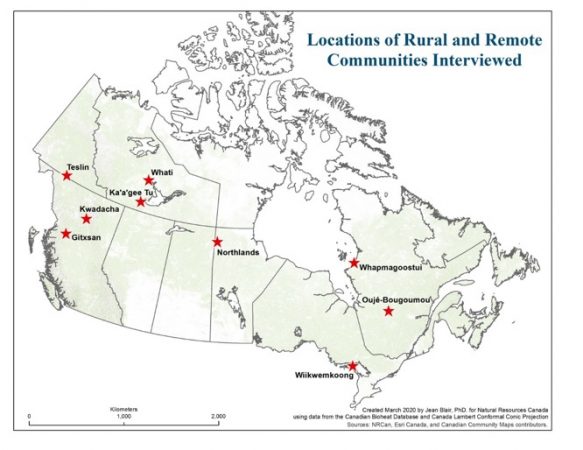

In early 2020, CanmetENERGY, part of Natural Resources Canada, carried out phone interviews with nine pioneering rural and remote communities that have installed biomass heating and CHP systems to learn about their experiences. Of particular interest were the unique challenges faced by remote communities related to all aspects of project planning, operation and feedstock supply, and how these challenges were overcome.

This article provides a brief overview of the communities interviewed, their motivations for developing biomass energy systems and factors that have led to success. Three spotlight articles, to be published on www.canadianbiomassmagazine.ca, will follow, detailing 1) technical and operations aspects; 2) fuel and supply chains, and 3) training and capacity building efforts in each of the communities. It is our hope that this series of articles will disseminate the knowledge gathered from these interviews for the benefit of communities who are interested in pursuing a biomass heating or CHP project.

Key characteristics

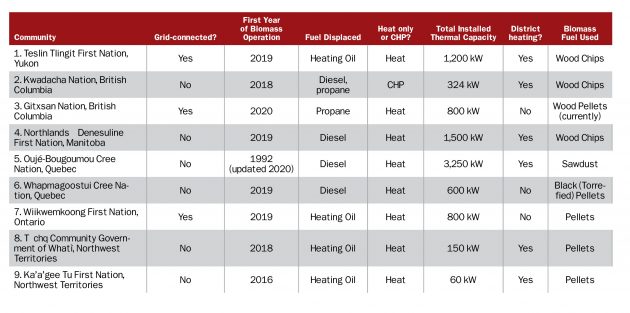

All nine communities surveyed are Indigenous and cover a wide geographical area. Eight of the nine communities are located in the far north. Six are off-grid and have diesel generating systems, while three are connected to the provincial electricity grid. All are reliant on heating oil, diesel or propane for building heat. In some communities, the biomass systems heat buildings connected to a district heating network, while in others the boilers heat individual buildings. One community interviewed has installed, and is successfully operating, a biomass CHP system – the only application of biomass CHP in a remote Canadian community to date. All bioheat systems greater than 150 kW use multiple boilers for improved efficiency and redundancy, which is important in remote communities where parts may be weeks away. The biomass fuels used include locally-sourced wood chips, sawmill residues, bulk-delivered wood pellets and black or torrefied wood pellets. A summary of the communities interviewed, and their bioenergy systems, is provided in the table below.

Primary motivations

While each community had unique reasons for pursuing bioenergy projects, in general the most important drivers were related to energy self-sufficiency and local economic development. Cost savings were a driver for some communities, especially those using wood pellets. Communities that developed local wood chip supply chains mostly reported creating opportunities for locals and taking control of energy production as more important than cost savings.

Other drivers reported include living off the land in a sustainable manner and reducing ecological footprints and health risks related to the burning of fossil fuels and diesel contamination. Greenhouse gas emission reduction, while important for higher levels of government, was generally not reported as a driver of biomass energy development at the community level.

Factors for success

Each of the communities interviewed has experienced challenges related to system design, operations, fuel quality and supply, and trained capacity, but each has developed plans or taken actions to overcome these challenges. What follows is a summary of the factors (listed in the typical phases of implementing a bioenergy project) that led to success in these communities and lessons that other remote communities can draw on.

1. Financial support

Biomass energy systems, and all of the auxiliary equipment related to biomass fuel supply, require higher capital than small communities have available. Government funding programs for financial support are therefore critical. All of the communities interviewed received funding to help cover the capital cost of the biomass systems; most received more than 50 per cent of the capital. Funding was drawn from a variety of federal and provincial programs.

2. Involve experts in system design

There is lack of expertise in remote communities to size and design mechanical and electrical aspects of biomass and (low temperature) district heating systems. Engineers that do not have specific experience with bioenergy tend to over-engineer and over-complicate system designs. District heating networks must also be appropriately sized for the heat loads of the buildings to maintain pressure and temperature differentials. It is therefore crucial for communities to seek the support of bioenergy and district heating experts in system design.

3. Biomass fuel and supply chain

The decision on what type of biomass fuel to use lies with the community and depends on local availability. For very remote communities, it also depends on delivery frequency and storage characteristics of the fuel over multiple heating seasons. Regardless of the fuel being used, quality and consistency are key to successful boiler operation; supply chain and quality control must be planned from the outset of the project. If there is an active forest industry in the region and sawmill or harvest residues can be sourced, this is generally the lowest cost feedstock. Communities that have access to bulk wood pellet distribution (but not residues) will generally choose to use pellets over establishing their own wood chip supply chain as the cost of the latter ends up being higher than pellets. Communities without access to forest residues or bulk pellets have established their own local wood chip supply chains. For communities above treeline and accessible by winter road only, torrefied pellets may be an option to consider because of the improved storage characteristics.

4. Technical support from suppliers

When sourcing the boiler/CHP equipment, it is important to consider the training and technical support that the supplier or contractor will provide. In most communities interviewed, the equipment supplier (and/or contractor) involved locals in the installation of the system and provided initial operational training. Some also provided follow-up training and on-going technical support, while other communities now rely on technical support from manufacturers in Europe.

5. Trained and skilled operators

A critically important – and often overlooked – aspect of successful bioenergy deployment in remote communities is ensuring that there is always a trained local operator on hand to address issues and carry out maintenance. For the systems that use wood pellets, having community staff operate the system (as part of their regular duties) seems to work alright but several have experienced challenges with high staff turnover and do not have a plan for on-going training. For systems with a local biomass supply chain where the log yard and chipper also need to be managed, having dedicated staff was crucial. Some communities are working on establishing more permanent training programs for their own communities as well as others in the region who follow suit. In general, respondents noted that the skills required to supply biomass and operate boilers fit well with local residents’ skill sets.

6. Community-owned infrastructure

In all communities interviewed, the biomass system and district heating networks are owned by the community. This is in contrast to the diesel generation systems in remote communities, which are owned by the provincial hydro company. Ownership of the bioenergy infrastructure gives communities an opportunity to generate income from the provision of heat (and, in the case of CHP, electricity) that can be re-invested into the community. Even if heating costs are not reduced, the money spent on heating is now kept within the community. Respondents also noted that biomass systems ideally are managed and operated by a corporation acting as a utility. This entity may be owned by the community but should be financially independent in order to have money available when needed.

7. Community support and local champion

Finally, no community energy project will ever be a success without the support of the community. Many communities were quick to welcome biomass heating as wood is traditionally used in the areas, while others were skeptical of the sustainability/viability of biomass as a local energy source. In most cases there was a project “champion” who helped get the community on board and pushed the project through hurdles. In some cases, the champion was someone from outside of the community with expertise in biomass heating, who saw an opportunity for the community and got locals on board through educating and building trust.

A positive step forward

These interviews have revealed that communities who have transitioned to modern, community-based biomass heating and CHP are driven by a strong desire to raise socioeconomic conditions in their communities and at the same time achieve energy autonomy. While their early operational experiences have generally been positive, there are still technological, infrastructure and capacity challenges that limit the acceptance and implementation of bioenergy in these rural and remote communities. For more detail on the technical and operations aspects, fuel and supply chains, and training and capacity building efforts of the communities, as well as the communities’ perspectives and experiences, head to www.canadianbiomassmagazine.ca to read the spotlight articles.

Read Part 2 of this series here.

Sebnem Madrali, Ph.D., is a senior research engineer at CanmetENERGY, Natural Resources Canada; her work focuses on advancing the development and implementation of heat and power generation from biomass and standardization of biomass fuels. Jean Blair, Ph.D., is a consultant and postdoctoral researcher who has been involved in biomass and bioenergy research for the past ten years, including the creation and maintenance of NRCan’s Canadian Bioheat Database.

This article is part of the Bioheat Week 2023. Read more articles about bioheat in Canada.

Print this page