What you don’t have, can’t leak: Q&A with Kayleigh Rayner Brown on process safety

April 8, 2021

By Gordon Murray, WPAC

Kayleigh Rayner Brown, P.Eng., M.A.Sc., research associate at Dalhousie University. Photo courtesy WPAC.

Kayleigh Rayner Brown, P.Eng., M.A.Sc., research associate at Dalhousie University. Photo courtesy WPAC. “What You Don’t Have, Can’t Leak,” is the title of a 1978 article by Trevor Kletz (1922 – 2013), a pioneer of Inherent Safety Design. He paved the way for a safer industry and for new trailblazers, including people like Kayleigh Rayner Brown, P.Eng., M.A.Sc., a research associate at Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S. Kayleigh has worked in the nuclear, petroleum and aerospace manufacturing industries with an environmental focus and, having completed a Master’s in process safety, is now leading hazard analyses in the pellet sector.

I have the honour of working with Kayleigh on the Critical Control Management (CCM) initiative currently being rolled out across Wood Pellet Association of Canada (WPAC) member facilities in British Columbia, in partnership with the BC Forest Safety Council (BCFSC). It will be a safety game changer for our industry and likely further afield.

I recently sat down with Kayleigh who had just presented some of her work at the recent Global Dust Safety Conference 2021.

First, let’s start with the obvious; what is Inherently Safer Design (ISD)?

ISD is based on four principles: minimization, substitution, moderation and simplification. Basically, it focuses on removing hazards so you don’t need to deal with them in the first place, rather than relying on extra equipment and procedures to be protected.

What’s an example of ISD?

Well, let’s start with a simple example we can all relate to: substituting a dangerous household cleaner that requires gloves and safety glass with a less-toxic cleaner.

At a pellet plant level, it could be using equipment that contains dust so it can’t escape and accumulate elsewhere. So, it’s really about getting rid of the problem ahead of time.

Why is it important?

Without ISD, we are opening industries to higher frequencies of Major Unwanted Events (MUE). One of the most tragic examples of this is the Bhopal gas tragedy. It happened at a pesticide plant in 1984 and more than half a million people were exposed to methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas and nearly 2,500 people died.

It was entirely preventable. They could have used a different manufacturing process or not have stored the chemical. On top of that, the installed safety devices weren’t working properly.

How did you become interested in ISD?

I grew up in a family who owns a fourth-generation logging business in Nova Scotia, so safety is a core value for us. I became an engineer because I’m interested in learning about why things are the way they are and how to make things better. Engineering makes me feel empowered to make a difference. While my expertise lies in ISD and bow tie analysis, I know that safety is about people as much as it is about science!

So, what’s the connection between ISD and Critical Control Management?

You use your process safety management system (PSM) to manage hazards and implement safeguards and controls. Inherently safer design is part of PSM and can be used to eliminate the hazards, so you are starting with a safer facility but you can still incorporate ISD in an existing facility by making changes.

Another important component of PSM is Critical Control Management, which helps us identify and manage our critical controls. Bow tie analysis is a powerful tool to help us do that. With the CCM in place we can assign accountabilities and a monitoring system to ensure those critical controls are managed.

What is Process Safety Management (PSM) – why is it important?

It is an organization’s all-encompassing program to ensure that people, property, the environment, and business operations are protected from loss-producing incidents. It includes a broad range of elements, from hazard analysis to safety culture to key performance indicators, which all work together to achieve safer operations, and includes all levels of a plant from leadership to the frontline workers.

How does Process Safety Management differ from traditional approaches?

For decades, we relied on the traditional approach to occupational health and safety where it looks at the responsibilities of workers and having a safety program in place. Process safety goes beyond that and tries to anticipate how all the processes interconnect and what could go wrong.

The fact is, you can be as personally safe as you want and wear your hard hat, your boots and all your PPE (personal protective equipment), but if the underlying process is not safe, you can still have a disaster like Deepwater Horizon. Sure, everybody was wearing their hard hats that day, but it unfortunately didn’t help.

Are there opportunities are for ISD for the wood pellet industry?

Absolutely! Moving dust collectors from inside a building or envelope to the outside. Another good example is that instead of minimizing hot work, what if we avoided it altogether and removed the ignition sources?

Are these types of actions being tracked and reported? Are there any leaders in ISD that stand out for you?

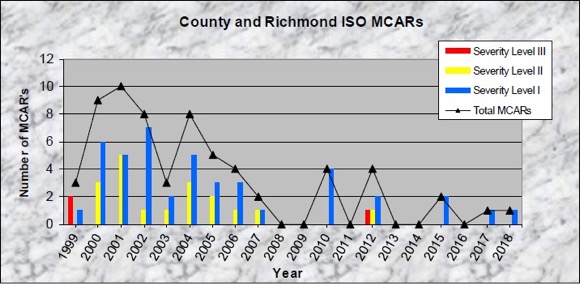

Yes, Contra Costa County in California. First, the Industrial Safety Ordinance (ISO) regulated facilities in the county in 1998. Facilities must communicate how they are incorporating ISD. This reporting is helping to expand our understanding of how ISD is being implemented and gives examples of how ISD can be applied in operating facilities, which has led to impressive safety improvements in the county.

Since 1998, there has been a downward trend in their loss producing incidents over the past 20 years.

A weighted score has been developed, giving more weight to the higher severity incidents and a lower weight to the less severe incidents. The purpose is to develop a metric of the overall process safety of facilities in the Country, the facilities that are covered by the County and the City of Richmond Industrial Safety Ordinances. A severity level III incident is given 9 points, severity level II is given 3 points and severity level I is given 1 point. Reference: Twentieth Anniversary of the Industrial Safety Ordinance Report, Contra Costa County Health Services, 2019.

Can you tell me about your current work with the pellet industry?

The project I’m working on, along with Eric Brideau and Dr. Paul Amyotte, is “Inherently Safer Bow Ties for Dust Hazard Analysis,” under an Innovation at Work (IAW) grant funded by WorkSafeBC. As part of WPAC’s and BCFSC’s Critical Control Management initiative, I am leading bow tie workshops for wood pellet facilities to develop bow ties for hammer mill, pelletizer, baghouse and silo storage. Now, Eric and I are examining these bow ties and identifying ways to incorporate ISD.

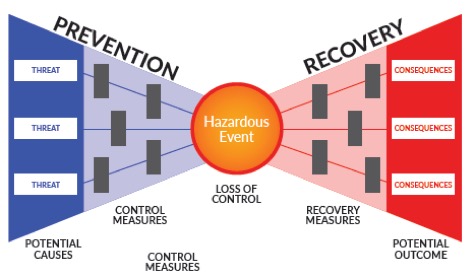

What is a bow tie – and how does it aid our understanding of safety?

It’s basically a visual tool that shows how a hazard could lead to a dangerous event like an explosion or fire. The Major Unwanted Event is the knot in the middle. The rest of the elements of the bow tie aid our understanding of safety because it allows us to assess how dangerous situations may arise and determine what controls we need to have in place in order to manage this risk.

What main areas of the plant are you looking at?

In an example of combustible dust in a hammer mill, which could lead to a dust explosion, we first need to understand how this could happen and how it could be prevented. We consider ignition sources, including prevention barriers such as rock traps and hot work programs.

Next, we think about what the consequences of a dust explosion would be and how they might be mitigated. We consider negative consequences, like harm to people and equipment, and examine mitigation barriers like emergency response plans and water deluge systems.

It’s really important to look at how prevention and mitigation barriers degrade and fail and how we can improve those efforts by practicing emergency drills and scheduling preventative maintenance for safety equipment.

What are the next steps for the Critical Control Management Initiative?

So far we’ve completed workshops at two facilities. Each workshop is five hours a day for a week. Because of the current pandemic, I’ve had to lead them virtually from the east coast, but the uptake has been great.

The workshop teams are made up of people with diverse knowledge bases and across all levels of leadership. I’m supported by BCFSC safety advisors Bill Laturnus and Tyler Bartels, who are providing on-site and online support to all 15 operations.

What’s the response been to this new concept?

The acceptance has been overwhelmingly positive. People immediately see the benefit of CCM, like a “head-slapping” moment where they bring up issues or opportunities they never saw before. It’s a great opportunity for staff to speak up to say what they are seeing.

How will you know if CCM has been successful?

I think when organizations are approaching safety with an inherent safety mindset, including when people are building facilities, or looking at management change or doing incident investigations or other opportunities they have to explicitly and routinely incorporate inherent safety design. And, of course, working with the other elements of process safety management, towards the ultimate goal of reducing the frequency of severe incidents.

A note from Gord:

WPAC and its members are proud to lead this work in partnership with the BCFSC and Dalhousie University, and Dust Safety Science, and with support from WorkSafeBC. The pellet sector has demonstrated leadership and commitment to continuous safety improvement when it comes to our facilities and the safety of our workforce. This pilot is ground-breaking work that I have no doubt will have broader benefits to the pellet sector across Canada and the forest sector. You can learn more about the pilot and schedule of workshops here.

Print this page